by William Wayland

Studio to Stage is a series that explores how music is made in the Bay Area. We follow local artists from the recording of their next single, EP, or LP all the way to the stage—and to their fans.

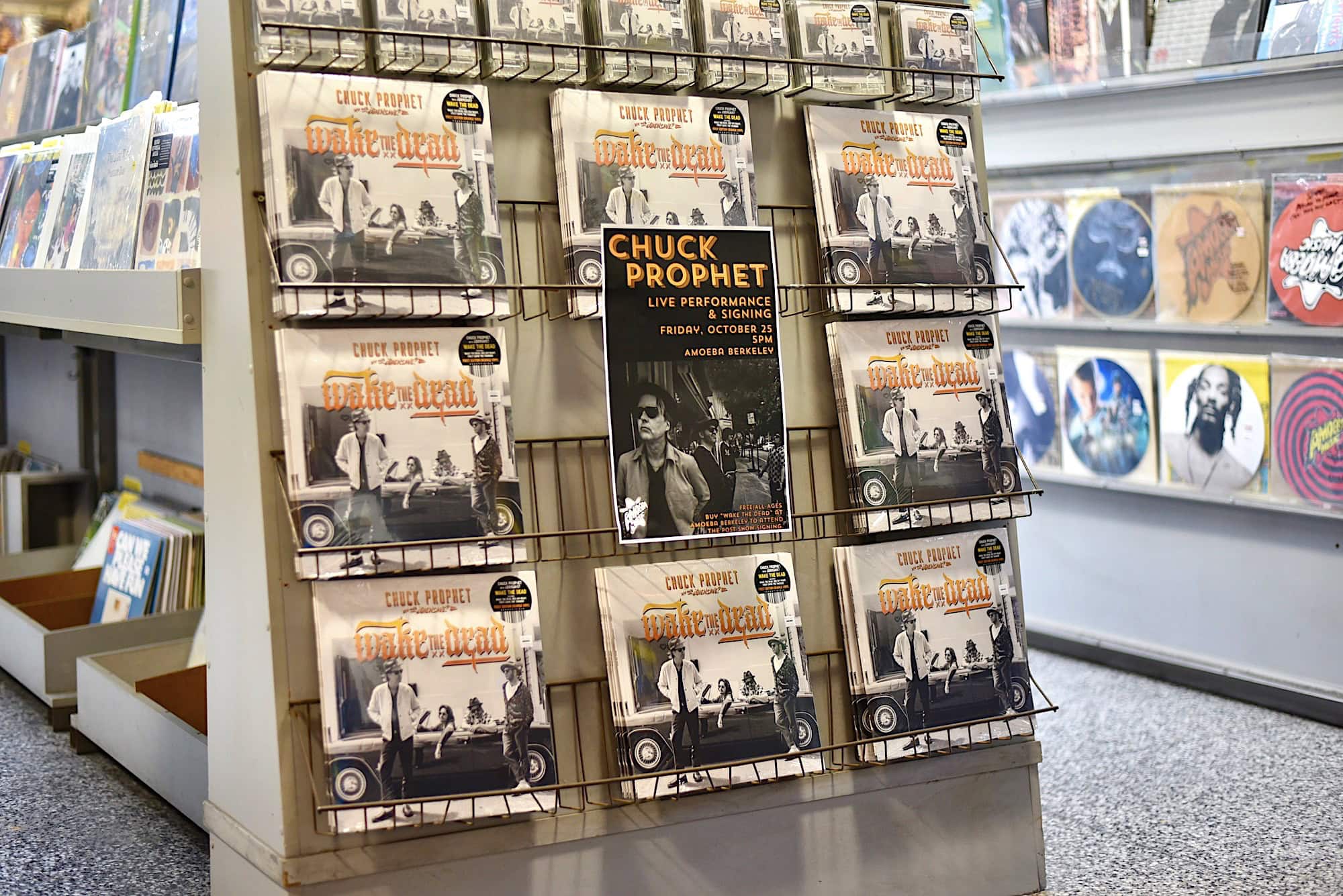

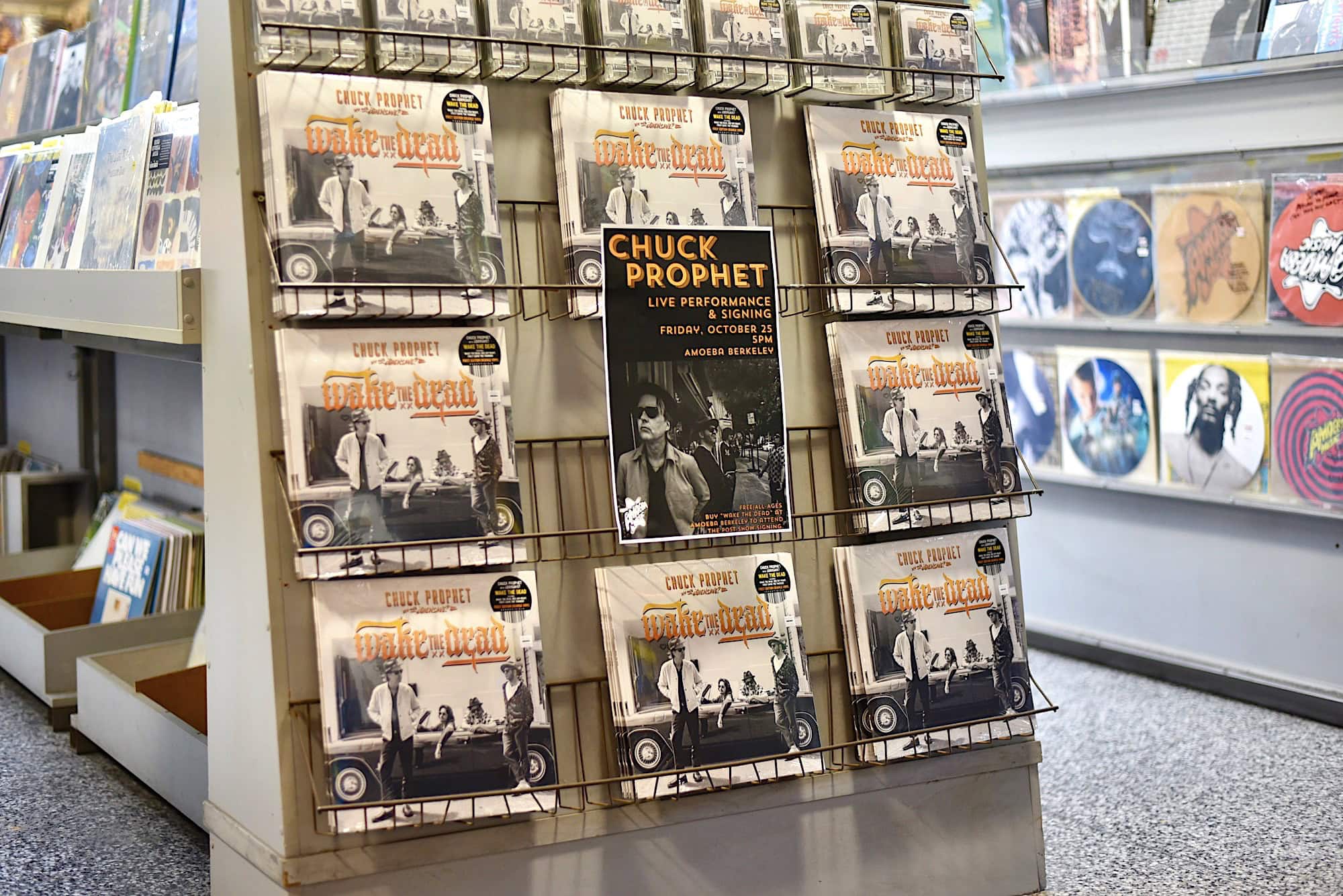

Record-making looks easy when Chuck Prophet does it. Inspired by his love for cumbia music, Chuck’s 15th studio album (27th album when you count live records plus his work with Green on Red) was released in October. It’s called Wake the Dead.

The eleven songs on Wake the Dead are still unmistakably Prophetesque and The Mission Express is there, too, but this album has a rhythmic cumbia flavor provided by members of Salinas band, ¿Qiensave? that make it the most danceable Chuck Prophet album ever and one of my favorite albums of the last year.

Last January (2024), I spent a week at 25th Street Recording to photograph the making of the album. Later, in October, I photographed its official release at Amoeba Records in Berkeley, and when Chuck Prophet and His Cumbia Shoes returned from the European leg of their tour, I went to see the band at the sold out Chapel show, something Chuck had never done before.

Before they begin the Eastern U.S. portion of the tour, I wanted to better understand Chuck’s creative process and how Wake the Dead came to be, so we sat down and talked about it.

The transcript of this interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

William Wayland: I think you said that you discovered cumbia at The Make Out Room, or at least that’s what I’ve heard. Is that where this journey starts?

Chuck Prophet: Well, my band was playing The Make Out during Hardly Strictly, and it was a Saturday night. They were rushing us to pack up our gear because there was going to be a dance party after the show.

So we packed everything up and we were sitting in one of those Naugahyde booths, me, my wife Stephanie (Finch), and Vicente Rodriguez, our drummer from San Antonio. We were having a beer or a Diet Coke or whatever, and this cumbia DJ shows up. Every Saturday night. And the place starts filling up, and here comes this bass line and Vicente started showing Stephanie some dance steps and I was just . . . enchanted . . . you know, I don’t know the word.

That night kinda started it. My love affair with cumbia. And then came the pandemic and the lockdown game. I was doing a lot of listening and I had a DJ show and, you know, you can find a lot of playlists online.

So I would watch a band on YouTube playing with an accordion and an electric guitar. A lot of great stuff like that. Really fascinating. I became a bit of an evangelist. I wanted all my friends to listen to it. I wanted to be a guide to this incredible music.

And those elements started to show up in my songs and I took it as a challenge, whatever that means.

I knew some producers that I thought might be able to help, so I visited with Adrian Quesada (known for his work with The Black Pumas), who’s an outstanding producer in Austin. I went to his studio and played him some demos. He had some scheduling issues and didn’t think he could work on it at the time, but he said something in that conversation. He said, people are going to tell you there’s a correct way to do this, you know, but you should do it your way. Just keep going.

WW: And there was a big gap between The Land That Time Forgot and Wake The Dead. Can you talk about that? Why was that?

CP: Yeah, there was a four-year gap. When I was in Green on Red we would release a record every nine months and then when I went solo it’s been every two years or so.

The way I know how to make a record is if I can tap into two or three songs that go somewhere I haven’t been before, then I get excited. I wake up to what I’m doing. And if I wake up interested in what I’m doing, I got a shot.

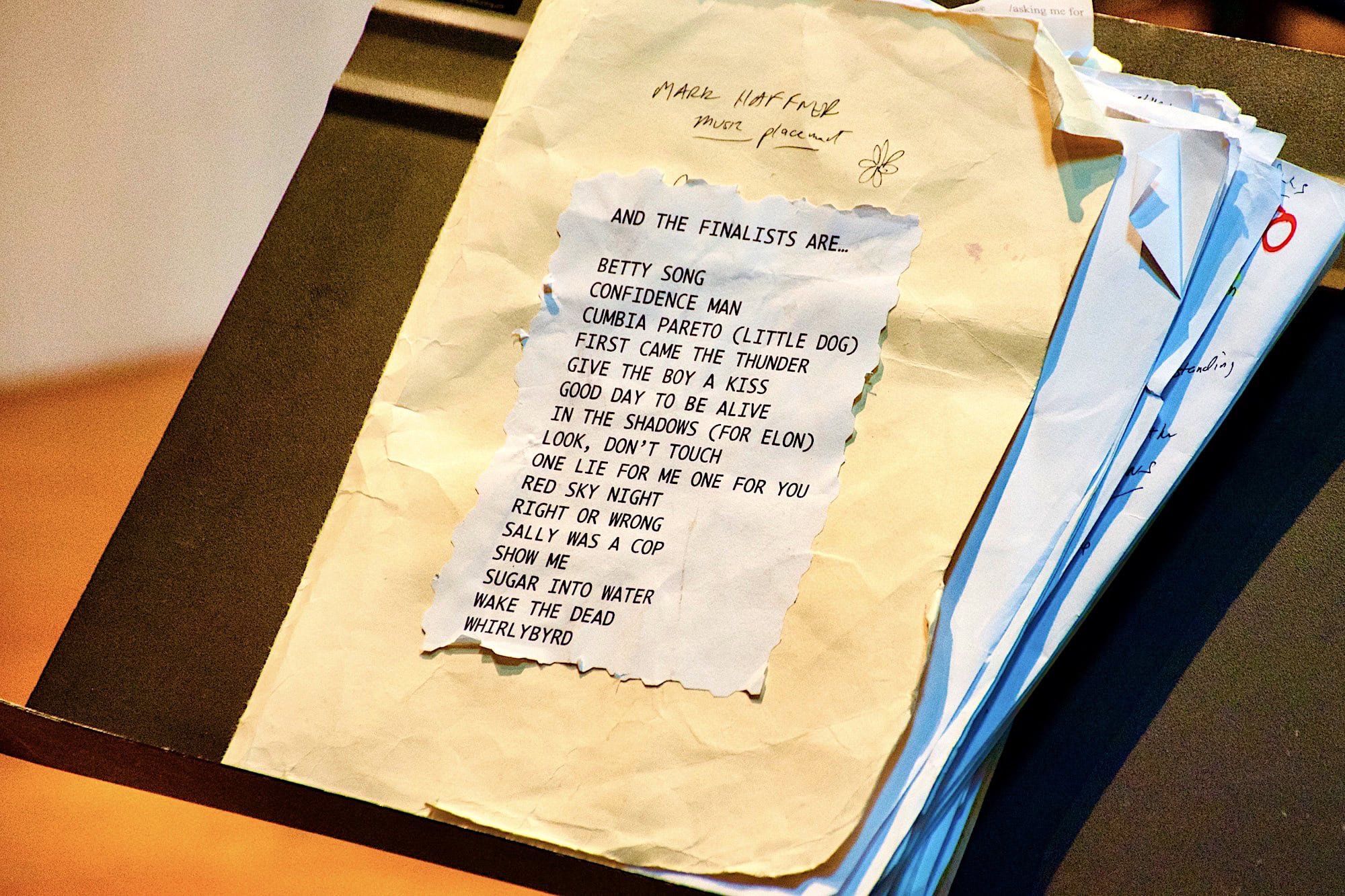

So, in this case, it took some time, but I just followed the needs of songs, and that’s how I got there. I ended up writing thirty songs. I co-wrote a lot of them with my friend Kurt Lipschutz, also known as klipschutz. That’s his pen name.

Also in there, I was diagnosed with lymphoma and the only thing that got me out of my head during the chemo treatment was cumbia dub. No words. I can really get lost in that.

WW: That’s right. Oh yeah. Are you cancer free now?

CP: Yeah, I’m in remission. You know, they’re watching it. I’ll have to monitor it for the rest of my life.

WW: So, about how much time passed between when you had that moment at the Make Out Room and the recording of the album?

CP: I would say I started working on the demos in February ‘22. We were playing in Austin, and I stayed on a few days. I went into Matt Winegar’s studio there, and we had a couple local musicians, a player from San Antonio. And so we brought people together and started feeling out some of these songs.

There were a lot of twists and turns in the road. I was just feeling around in the dark, and listening to records and trying to figure out how to do this in a way that made sense to me, you know?

WW: When it made sense to you, how much of Wake The Dead felt like a Chuck Prophet record and how much of it felt like a cumbia record? Because it feels like a departure to me. And I think that’s what’s so interesting about it.

CP: Well, we have these devices like bridges and choruses and intros and outros. And the cool down in the third verse. I don’t know where they come from, probably the Brill Building or whatever, but all these devices that we use to arrange songs and keep the listener interested, you know, like you give somebody a verse, and then immediately you give them some information, and then you give them another verse, more information, and then you give them the cookie before it. Then you take the cookie away and then, hey, go to a bridge.

But, you know, a lot of the time if you listen to early cumbia music, it’s just one chord. One chord and no bridge. So I’m looking at all of these devices from a different perspective, literally.

Some of it goes out the window, but a lot of it doesn’t go out the window. And that’s why, when I delivered the record to my label, they were somewhat relieved because they thought it was going to be . . .

WW: A traditional cumbia record?

CP: Right. And they’re like, oh, this sounds like Chuck Prophet. So there was a lot of relief. I can’t let go of all that.

WW: And that answers my question. You took this music. You were inspired by it and it led you to the Wake The Dead Sessions.

CP: Yeah. Kind of like a mad scientist with the beakers and the smoke coming out, you know?

But, you know, there’s another critical element that I kept in the back of my mind, and that is when i started jamming with ¿Qiensave?, who are brothers from Salinas, California.

My manager, Daniel, saw them play, and I went and saw them and I was really charmed by them. I asked a bunch of questions and they said, Well, you know, if you want to come hang out with us sometime, we have a pad in the woods and you can turn your guitar up as loud as you want and I took them up on that, and that was one of the things that really helped me when I was getting treatment because treatment is the blues, man.

So I would get my longboard and drive down to Santa Cruz. One time I spent a whole weekend there jamming with them. It was kind of slow going, trying to find where their music and my music overlap, and it was cool, you know, and they were just affable guys. And then I got offered to play the Hipnic Festival but my band, The Mission Express, wasn’t available.

When I learned that, I was actually down in Salinas hanging out with ¿Qiensave? and I said, Hey, I haven’t really thought this through, but I just got an offer to play this festival, do you guys want to do it with me? It’s only a few minutes from here in Big Sur.

And they’re like, Is it some kind of hippie festival? Cause when we start playing the cumbia, the brown people are going to come out and start dancing.

And goddamn it if they weren’t right.

WW: That’s hilarious, yeah.

CP: So this goes back to your question of playing the music “correctly”. There was a moment when we were on stage and everybody was dancing. And for me, it was pretty magical.

It reminded me of my earliest punk rock shows. When I was 16, I would drive into the city and go to places like The Temple Beautiful and see bands, maybe The Flamin’ Groovies or whatever.

And what happened with punk rock is it eliminated the line between the stage and the audience because prior to punk rock, the rock gentry were living up in their castles and punk rock came and stripped everything back to the drywall.

That’s the way it felt when everybody was dancing. What was happening in the audience was just as important as what was happening on the stage.

And so you asked me, how did you get there and how much of the record is cumbia and how much of the record is Chuck Prophet and to answer your question, when we played at The Alive and Kicking (𝐁𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐟𝐢𝐭 𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐫𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐏𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐞𝐫-𝐖𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐢 𝐇𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐂𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐧𝐢𝐚) at Great American with Commander Cody and Dave Alvin and The Lost Planet Airmen, it was so gratifying when halfway through our first song I could see the audience really moving. I think cumbia speaks a universal language and it really translated.

WW: Did you have the full ¿Qiensave? band there?

CP: That night I had two members of ¿Qiensave? and also Joaquin Zamudio Garcia from Mexico City, my rock, my bass player.

He’s spent a lot of time in Tucson, where I have some history and he’s really the foundation for the record and everything.

WW: Right. I remember Joaquin from the recording at 25th Street. His amplifier was in the hallway and there were times when I was outside of the studio and all I could hear was this infectious bassline. It was hard to concentrate on anything else.

CP: Everything is centered around Joaquin.

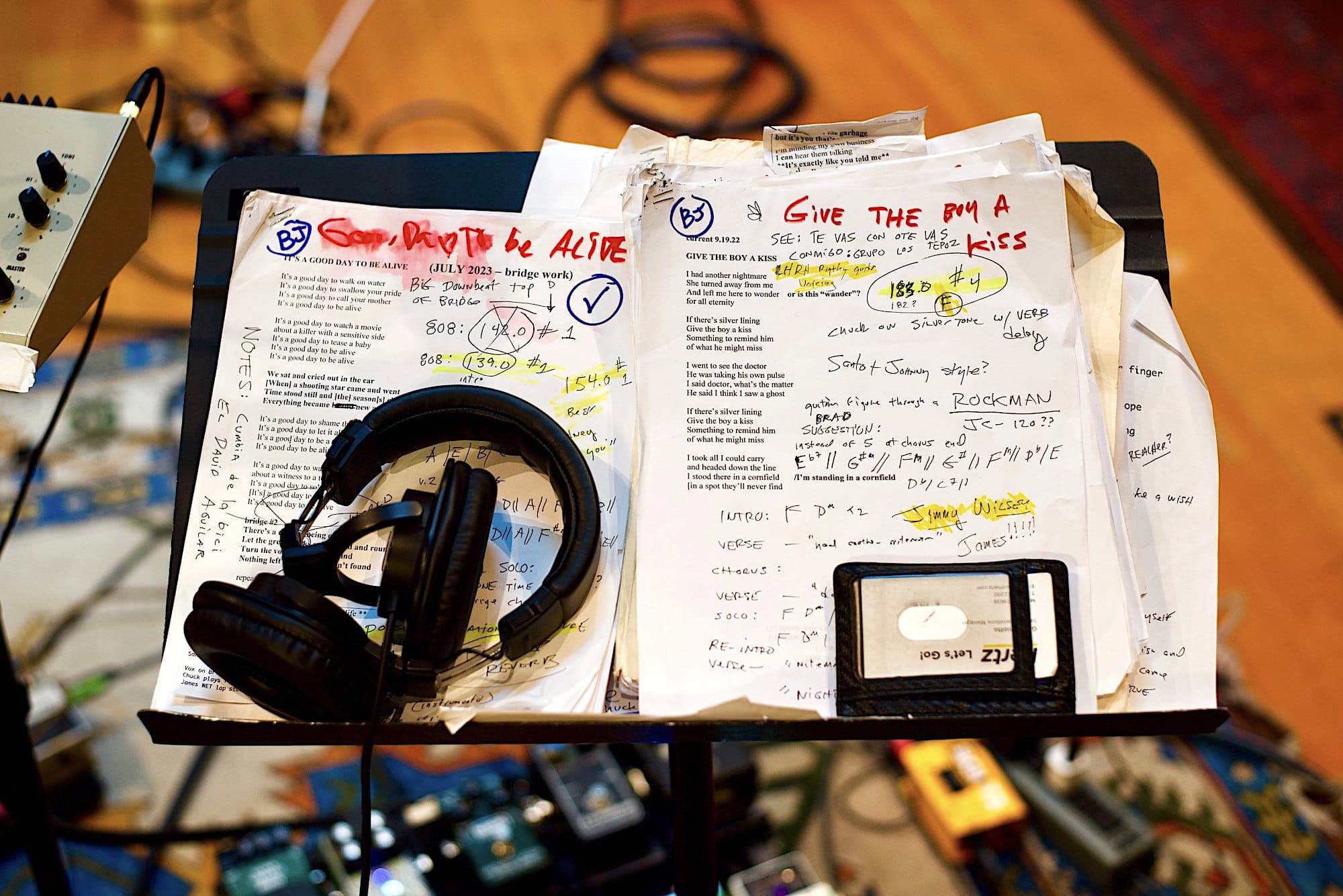

WW: I want to ask you about the recording process. It felt like you had the entire album mapped out. You seemed to do one song in the morning and one song in the afternoon. You might try a few things but it felt like you had it pretty much worked out. Is that how it felt for you?

CP: You know, in film, people always think that movies are made on the set and if you talk to the cinematographer, they’d probably agree with that. You talk to the actor and they’d tell you that, you know, it all happens on the set. It’s either in the script or it’s not.

I did have the songs pretty mapped out. I’d done my best to iron out whatever wrinkles there might be. I was able to sing the songs and I had the lyrics finished. I was responsible, you know.

Because I haven’t always been that way. When I was in Green on Red, we had a smart ass answer when people would ask What comes first, the music or the lyrics? We always said, Oh, that’s easy, the event. But that was the time and we weren’t always ready to go.

You know, I find that the more prepared you are then the less time you have to prepare in the execution part.

I’m less enamored with Hey, let’s run that through a phase shifter, let’s double it, and all that stuff.

25th Street is such a nice studio that it could be problematic.

WW: Because they’ve got so many toys to play with?

CP: That’s part of it but it’s just real comfortable there. They adjust the lights real nice. They got those nice leather couches.

WW: They make you feel like you want to camp out there for a couple of weeks?

CP: Yeah, I think it’s much better now.

WW: By my count, I think you’ve made twenty-seven records.

CP: I’ve made a lot of records. But that’s the thing. Back then, records were not so much finished as abandoned. You’re up ‘til five in the morning trying to get a mix and then eventually you just surrender. So it was great but it wasn’t always great.

The editing we do now, you know, it’s so easy to make the smallest edit.

If I’m producing a band with two guitars, a bass, drums. I’ve got my headphones on. I’m playing guitar. I know everything’s going on. I can tell you where a player is on the neck of their instrument and I can say, Hey, why don’t you pedal the bridge, or something like that, you know.

But when you’ve got eight or nine people playing cumbia, all I’m doing is performing. I’m just letting go. There’s no way I can put my fingerprints on everything. We’re just going down the road. So that was a new experience for me and it was certainly scary in many ways but still a lot of fun.

WW: There’s something that I love about an album that doesn’t doesn’t sound overly produced. That’s part of the magic of Wake the Dead.

I didn’t hear the album until it was finished, about ten months after the recording. I know a lot of work goes into a record in post but it doesn’t feel too different from playback in the studio. You didn’t go back later to add layers of vocals or instrumentation.

CP: The temptation is to fix the mistakes, but that can be a troubled path. I feel like an abstract expressionist painter with music in many ways. I’m lucky to have relationships with people like Brad Jones. We’ve worked together a lot. We understand each other, and there’s a trust there. And we have faith. Maybe something doesn’t sound good today. It’ll sound good tomorrow. Because of the process. We have faith in that process. And we have trust in each other.

How many records have you made with Brad?

CP: Oh, I don’t know, Soap and Water, Temple Beautiful, Night Surfer, Bobby Fuller. And this one, I guess that’s number five?

WW: I loved Brad’s confidence. I’ve worked with producers that are afraid of the sound my camera makes when I shoot. Brad was like, Go for it, and I had to ask, Are you sure? And I made the camera click, and he said Go for it!

CP: Well, I’m a performer. And everyone in the group, they’re performers. They like the camera.

When I’m in the studio, I’m performing right then and there. I’m highly sensitive. Other people are wagging their tails or they’re not. I’m sensitive to that stuff. I’m very sensitive when I go into the control room. I’m looking around. If everybody’s kinda wagging their tails and happy then I know I’m in the zone, and then it’s a matter of getting a great performance. It may not be the definitive performance. The definitive performance could come on some stage at a festival in Rochester, New York or something in 110 degrees humidity, I don’t know, but I’m always going for it.

And I don’t know if it’s going to be definitive. Few people made definitive records. I think The Beatles made definitive records. Bob Dylan, as we know, the definitive version might be on some outtake that we won’t hear until 30 years after, and that’s sort of the beauty of it.

WW: Do you think Chuck Prophet fans are going to go, what is this? With this new record?

CP: Well, you know, I tour the singer-songwriter circuit like The Rams Head in Annapolis and all the City Winery venues in Atlanta and New York. We’ll play multiple nights at The Continental Club in Austin. I’m really comfortable in a lot of those venues, but I think this music is made for dancing so I hope to play more outdoor festivals. It could be Idaho, Tuesdays in The Square, and maybe play to audiences that don’t know my discography. We’ll surprise them. I feel like cumbia is a universal language and when it works nobody needs to know who the band is. That’s something that I aspire to.

WW: So, you’re touring now to support Wake the Dead. Are you already writing songs for your next album?

CP: No, I don’t do that so much anymore. I have a lot of people in my life that when we get together we know, like when you put two wires together, we know that it’ll happen.

I’m not writing every day. If I was going to write with somebody like Kim Richey, who I wrote Red Sky Night off the new album with, you know, I would probably be somewhat prepared. That’s my nature, you know. Maybe bring a couple of ideas. Just have them up my sleeve so we’re not just sitting there staring at each other. But at the moment, I’m not in that mode of my life where I’m wrestling ideas to the ground.

I am thinking about the next record and I hope it doesn’t take me four years.

WW: So, would you do another cumbia record?

CP: Yeah.

If it has a hold on me or a desire or it’s what I’m feeling.

I may learn more about the songs on the record by playing them for people every night on the bandstand.

WW: When you play them live every night, it’s a different thing. Do you have a favorite song on the album?

I like the way “Wake The Dead” opens the record. I think it makes a statement. You got those quarter notes that come out of nowhere. There’s a timbales feel. And then in a few seconds you’ve entered into the world of Wake The Dead.

I’m proud of that. It would be great to have something strong to open the record and there it was.

And I knew “It’s a Good Day to Be Alive” would close the record, and so, those two are my favorites.

WW: I think “Wake the Dead” is my current favorite. I keep going back and forth but that’s my favorite this morning. It’s got this bad assery about it that I like. It’s a little criminal. It’s a little badass. It’s a little bit of a statement.

At the end of every session, I’d go home and I’d be humming whatever the last song you guys were playing that day.

CP: Yeah, me too.

WW: At the end of every day I would think, man, they’ve got something going on in there. Thanks for doing this interview.

CP: Thank you, William, it was fun.

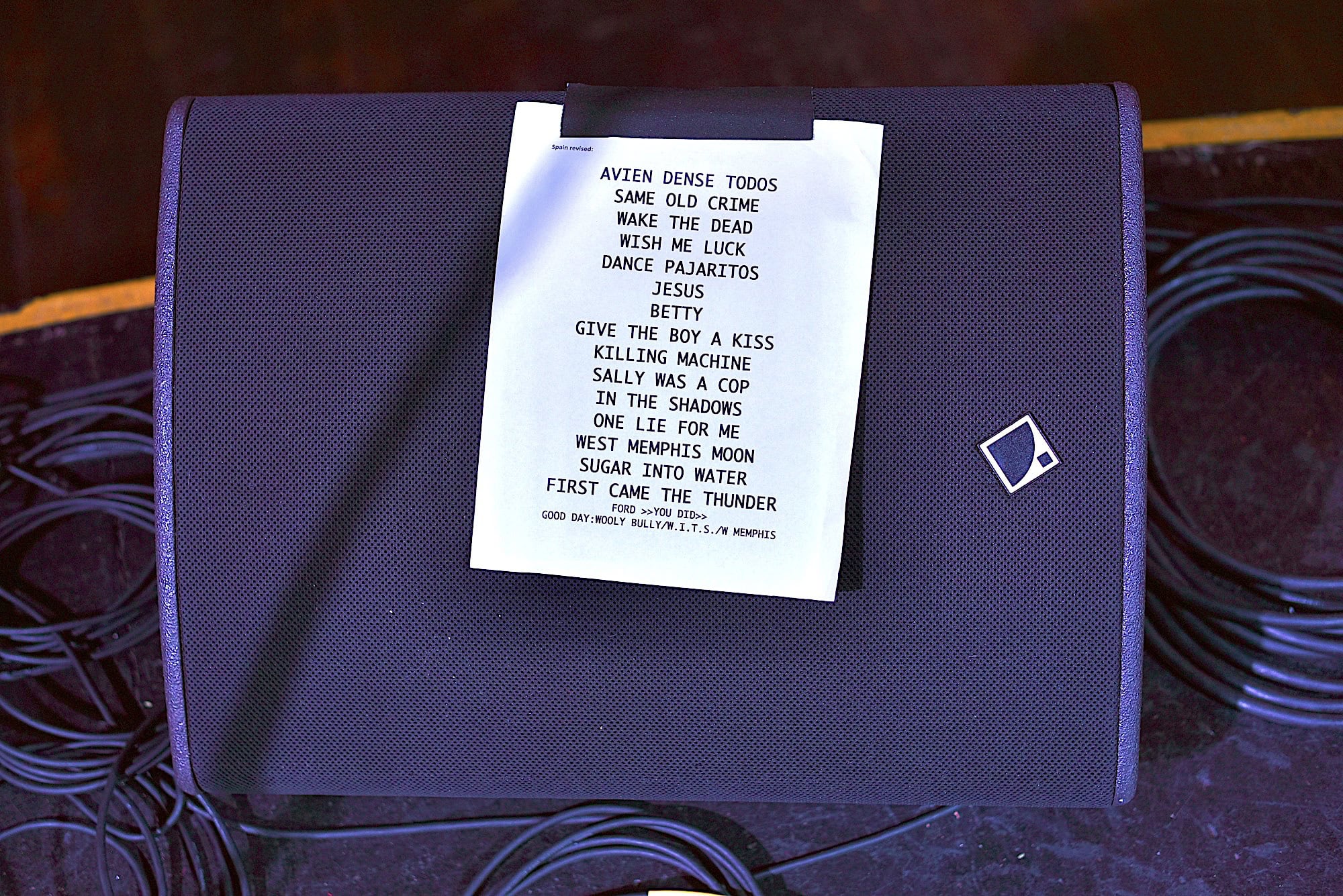

If you want to hear Chuck Prophet and his Cumbia Shoes live, they continue their Wake The Dead tour to the Eastern US through mid-February, and then they go on to tour the UK.

Are you making music in the Bay Area? If you’d like to be considered for a future Studio to Stage feature, reach out to William Wayland.

Wake the Dead Sessions: 25th Street Recording, January 23-27, 2024

Amoeba Records in Berkeley: October 25, 2024

The Chapel: December 28, 2024

Leave a reply