Interview and Photography by William Wayland

Chris Peck might be the most prolific Bay Area songwriter and musician you’ve never heard.

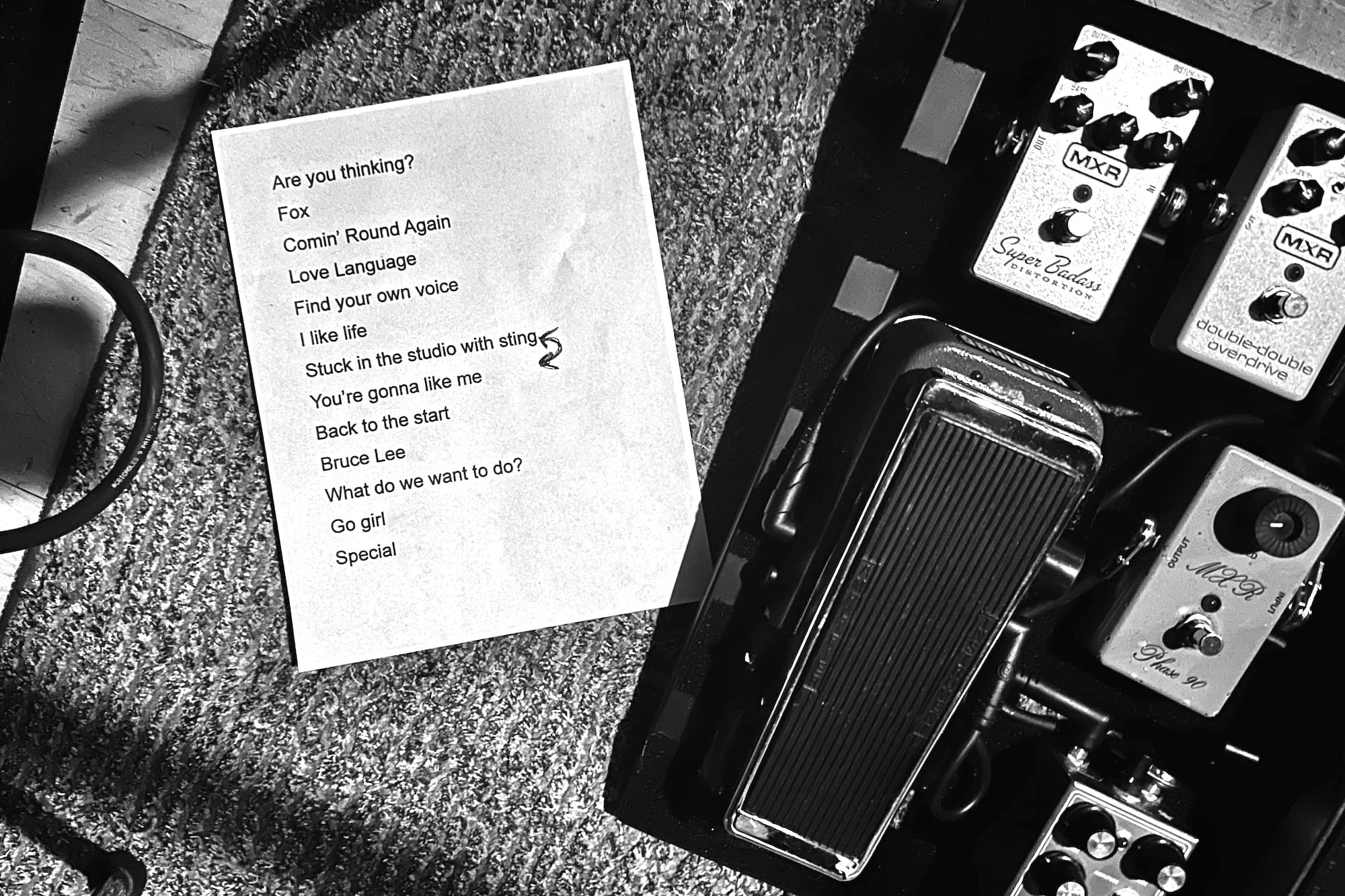

To me, he’s a musician’s musician because his music feels both simple and disarmingly complex at the same time. He has the ability to write songs about texting with a “Truther Babe” or being “Stuck in the Studio with Sting.” In each, the lyrics weave stories that feel too specific to be fiction. Are they?

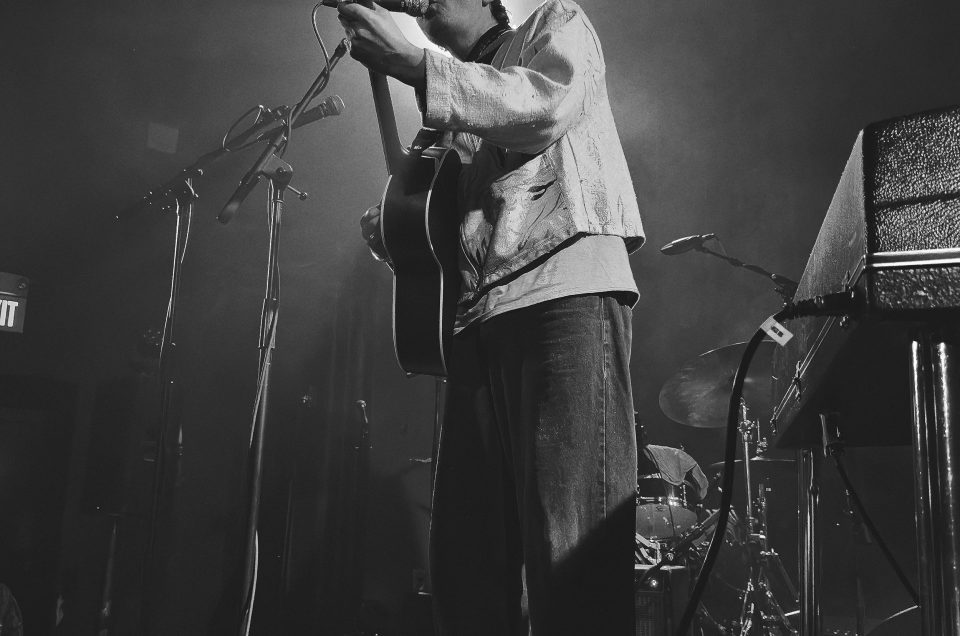

Last Thursday, Chris released his twenty-fifth (but first solo) album, Exact Change, at Peri’s Tavern in Fairfax. He played a solo set followed by a set with the full band.

After the show, I spoke with him about making music and making albums.

William: So, why do you make music?

Chris: It started early for me. Even before I could play an instrument, I was pretending to play. MTV was kind of holy for my friends and I.

Okay, I get that you got the music bug early but that doesn’t really answer the question, “Why?” Unless you’re Taylor Swift, it’s incredibly difficult to make a living at it. You even allude to this in the lyrics of “I Love Money,” when you sing,

You’re so good /

And I love what you do /

And I wanna support you /

Here’s some loot

I don’t think that’s just a throwaway. So, what is it that makes you make music? Why this addiction to creating an album every year and four days? I did the math.

Thanks for digging into this.

I got very lucky in my formative years as a musician here in Marin. There’s always been a strong webbing between adult and youth musicians in this county, and I really benefited from that. Not only did I have some really potent and positive teachers – Bruce Munson, Jackie King, John Gorrindo, and Jimmy Sage all come to mind – but I also got to mix it up with musicians out in the wild. On stages, in festival parking lots, in rehearsal rooms, and in recording studios. All of those moments of mentorship from elders and also kinship with players closer to my own age . . . they’re still so sharp in my memory.

I got to be part of a genuine culture. Something real and not manufactured. As a result, my whole skillset and really my whole being was formed around the act of making and listening to music.

So, like a racehorse loves to run, I think a player loves to play. If you take that horse out of the racing life, they get barn sour and despondent.

Also, I’ll probably never quit the musician life because I’ve almost lost it a couple times. When I was 20 years old, I had a really bad repetitive stress injury while my friends and I were building a rehearsal studio in Brooklyn.

After a summer of construction work, it suddenly hurt to play instruments, to type an email, to lift anything moderately heavy, or even to turn a key in a door. That phase was a real journey, and it took me about five years to come back to performing and recording regularly. I spent those years, my time in the wilderness, searching for a way to continue being musical. Making electronic music, notating music for other people to play, picking up new instruments that seemed to strain my body less, beat-boxing, and singing into a looping pedal, going out to dance a lot, and working on my own performance style as a mover/dancer, and finally, making music that consisted of spoken vocals only, performed without musical accompaniment at the 16th & Mission open mic on Thursday Nights. It was the discovery of that open mic when I was 25, that brought me back to performing regularly and really being a fully active musician again.

Those five years were a tough time, and in that time I experienced what it’s like to be separated from the act of music making. There have been a couple other chapters, shorter, but also health-related, where I needed to pull back from the musician’s life. They’ve all added up to give me kind of a permanent hunger for this musical journey.

So even as the avenues of remuneration are constantly shifting, and some would say contracting, in the music business, and even as it gets harder to compete with newer, brighter, more addictive, and more visual forms of entertainment, I feel more and more like a music maker, a music lover, and a musician defender as the years and now decades flow on.

Thanks for that, Chris. I hate to pigeonhole musicians on their sound but I also somehow feel like I need to describe what I hear to someone who doesn’t know your music. To me, there’s a Steely Dan-meets-the-Conchords vibe. I say that because there’s a jazz aspect plus stories in your music, and that feels very Steely Dan, which I’m a huge fan of. But there’s also what feels like intentional humor–maybe more so with this latest release. Could you comment on that? Feel free to tell me I’m wrong.

I love Steely Dan. I haven’t heard much from Flight of the Conchords yet, but I know that their music is super fun and humorous, and that is definitely a side of my writing, too. The funny side of my writing seems to come and go. In my late 20’s, I was writing a lot of raps, and I really enjoyed putting some ribaldry into those songs. The funny stuff seems to be back on Exact Change.

In the last decade or so, I’ve fallen in love with a string of albums that have taken me back to the heart of rock and roll. Electric Warrior by T.Rex, Troubadour by J.J.Cale, Dreaming My Dreams by Waylon Jennings, Dirt Floor by Chris Whitley, and most recently In Color by Cheap Trick.

All those albums sort of carried me into middle age, and gave me a willingness to embrace tradition and depth, and grow away from the raging appetite for progress and newness that characterized my 20’s and early 30’s.

Dirt Floor, by the way, is a solo performance album and is definitely a template for Exact Change. Ethan Turner, who mixed Exact Change, turned me on to Dirt Floor. It’s so beautiful and kind of universal in its appeal. I recommend it to people all the time.

You produce so much. Are you writing all the time or do you need to dedicate time to it?

Increasingly, I need to carve out dedicated time to write. In April of 2020, I started a Patreon campaign and promised my supporters that I would write two new songs a month. That’s been a great accountability buddy.

When we were talking earlier, you talked about the community of musicians and you described how special that is for you. Can you tell me a little more about that?

Musicians and music lovers are my people. We hold the same things sacred. Players, songwriters, record store owners, people in radio, music writers, people who repair instruments, recording engineers, music publishers. We all come together to make an ecosystem. After Napster arrived, and then Limewire, and then the iPod, and now streaming, I feel like that circle grew even tighter and more interdependent.

I think what you do is form a new band for each release.

For example, I remember when you would perform as Chris Peck and Sparkling Water after Sparkling Water was released.

Explain that to me.

That’s been true for a long time. Now, though, the Sparkling Water Band has outlived the Sparkling Water album release cycle. We’re growing closer as a unit, and we’re halfway done recording a live album at the Papermill Creek Saloon, which will be the next record to hit the streets. It’ll have five or six tunes that are brand new, and some familiar songs with a new strut to them.

You’re already working on a new album and “Exact Change” is only a couple days old.

You’ve released 25 albums going back to 1994. What do you like about creating albums? Is there something about creating a goal?

It’s kind of a compulsion. I liken it to a gambling addiction. As soon as one album is done, my subconscious starts assembling the pieces of the next one.

What’s the concept? Which songs? Who’s gonna play on it? How and where will it get recorded? Are we putting it out on vinyl or cd or cassette or digital only? Are we making music videos? Are we touring? Where’s the release party going to be?

After it’s over, I rest for about a day, and the thing starts again.

How is “Exact Change” a departure from your previous work? Is it your first solo album? I don’t actually know.

Exact Change is certainly a departure.

It’s my first solo performance album, and in that way, it’s sort of anti-production: no overdubs, no edits, no horns, strings, or percussion arrangements. No fireworks outside the realm of what one person can do alone in front of a microphone.

The making of Exact Change was definitely a group effort, though. The project really began when a few friends of mine assembled a unique recording rig. Miles Wick, Alex Rather Taylor, and Luke Westbrook are all close friends of mine, and a few years ago the three of them got very interested in something called DSD recording. It’s basically a very hi-fi one-bit digital recording, that is usually only employed for live capture. Symphonies, jazz, Indian classical music.

My three buddies invested in a few DSD units, found some very special preamps, and learned to hand-wire a few microphones. When the whole rig was up and running they suggested that I come in and record some of my songs. I had about fourteen new ones that I thought would make a good solo performance album. We met up three times. Twice in Sonoma and once in Elgin, Texas, where Miles had moved, and recorded several takes of each tune until we all felt like we had a record.

We also recorded some other songs in the same time period. All three of those guys are very special musicians and we took turns recording each other’s songs or ideas. It feels like Exact Change is just the beginning of a whole DSD phase for us as a crew. Maybe a record label or some other kind of collective is taking shape around this methodology.

I love hearing a completely live recording. It takes me back to the roots of recorded music, thinking about the Anthology of American Folk Music, or the work of Alan Lomax, or the way that most jazz music is recorded. I think about Robert Johnson, who recorded twenty-nine songs in his twenty-seven years, all of them captured in two recording sessions in a couple of Texas hotel rooms. He was so seasoned as a performer that he could just sit in front of a microphone and make a seismic impact on the history of American music, all by his lonesome. I love that level of mastery. It’s something to aspire to, even if we’re living in a different era than he did.

I have one last question on Exact Change. You dedicated the album to Bruce Munson. Who is Bruce Munson?

Thanks for asking. Bruce was my music teacher at Branson High from 1994 to 1998. He had a huge effect on my friends and I, not only passing on the fundamentals of jazz music but also hipping me to a pantheon of musicians who are still among my favorites today: Weather Report, Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, Jaco Pastorius, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Allan Holdsworth… I could go on.

Bruce had a very interesting second career as a music engraver for the San Francisco Symphony, Gordon Getty, Stanly Clark, and many others. I had a second phase of tutelage with Bruce in my mid-30’s, working on a few projects that he’d hired me for, and going to dinner several times. In those dinner table conversations, always long and intensive, he revealed new levels of knowledge about music and the music business that I wouldn’t have grasped back in high school. He urged me to work hard, seek out my heroes, and look beyond the local.

Bruce passed away in the fall of ’22. I feel very lucky to have known him and have had two major phases of study with him.

Thanks Chris. I suppose I ought to tell people that Exact Change is available on Bandcamp, and probably a bunch of other places.

Comment

Excellent work, Mr. Wayland.